Claire Louise: They All Lied To Me

Claire Louise: They All Lied To Me

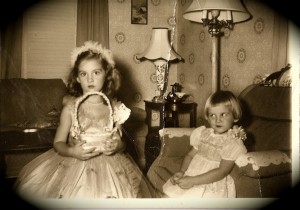

I’m working on SHADE ISLAND, sequel to my first novel and wondering what people think about this iteration of the Richards sisters twenty years after my readers first met Claire Louise and Macy Rose in Daughters of Memory, 1991. This chapter is told from older sister Claire Louise’s POV.

Macy suggested that I eat some of the barbecued chicken and sliced bread on my untouched plate to compensate for the wine that I’d been slugging down. She didn’t take kindly to my rejoinder that she was going to have a difficult time falling asleep if she didn’t lay off the iced tea, or to my statement that any nutrients that might have once existed in the wheat kernels used to make the bread were sure to have dissipated long before Mrs. Bairds’ manufacturing process turned the genetically modified cereal grain into processed white bread.

Curtis Oates, Jr. and his long-time girlfriend Nina returned to the table, both of them hot and sweaty, fresh off the dance floor where they’d been participating in the Cotton-Eyed Joe with at least one hundred of Crystal and Rocky’s wedding guests gathered at the Cypress Springs Fire Department. I wasn’t having all that great a time yet, but the night, as they say, was still young. Even though Cypress Springs is only a short twenty miles from Molly’s Point, where we still live, Macy and I hadn’t actually kept up with the San Miguel branch of our family after Grandma passed over ten years ago. The plain hard truth of the matter was we’d fallen out with Cousin Crystal’s mother, Aunt Vivian, over certain items that she appeared to have appropriated from Grandma’s house during her last several visits. Water under the bridge, as Grandma would no doubt say, and I was certainly willing to bury the hatchet if Aunt Vivian was, hence my presence at her daughter’s wedding.

Macy was sitting in one of metal folding chairs, her hands clasped together in her lap, looking all prim and proper. She isn’t now, nor has she ever been, what I’d describe as a party person. When her husband asked me if I wanted to dance the next dance with him, I opened my mouth to respond with one word: sure! Unlike my sister, I love to dance, however, at that exact same moment a man whom I initially believed to be a complete stranger to me approached our table, his hand outstretched in my direction and a goofy smile plastered all over his face. Carlton, who was already half-way out of his chair preparatory to getting me out on the dance floor, sank back down into his chair. The metal legs clanged as they raked over the concrete floor. “Go for it, Claire Louise” he said. He’d been out on the dance floor quite a bit already this evening and looked relieved to be able to sit down and pick up his glass of iced tea. My sister’s husband, who hails from out of state and, unlike almost the entire rest of the town of Molly’s Point, is a complete teetotaler, didn’t look tired so much as he was starting to look well, not to put too fine a point on it, he looked bored. Not that I know anything significant about his life prior to when he married my sister and moved with her to our small town, but I do know that he came from big city, and undoubtedly wasn’t used to weddings as down home as this one was turning out to be.

Floyd Romaine was a tall man, likely six feet five or six inches, I believed, and heavily built. At this point in the evening he appeared somewhat disheveled, almost unkempt. His left arm, which had likely been muscled at one time, felt to be composed of solidified lard as it rested across the tops of my shoulders. He pulled my body into his and squeezed the top of my left arm with a grip that was almost painful. I became uncomfortably aware of the sweat that had pooled in his armpit and saturated the underside of what was likely his best western shirt. I looked into his eyes, smiled, and tried unsuccessfully to separate my body from his. “Claire Louise Richards as I live and breathe,” he exhaled. If the quality of his breath was to be credited, he’d been hitting the beer keg to the exclusion of any other food or beverage for the past three hours.

“Floyd Romaine,” he continued, talking with an intensity that took me aback. “We used to ride the school bus together. My brother Lloyd was in your class. I am three years younger than you and Lloyd. But I remember you and your sister real well.” At that point, Floyd nodded his head at Macy, who looked stricken and anxiety-ridden and as if she had taken up permanent residence in that folding metal chair. She was sitting directly behind the spot on the edge of the dance floor where I stood and, in all honesty, resembled nothing so much as a guppy with her big eyes and wide-open mouth.

“Is that a fact?” I asked. I vaguely remembered a boy named Lloyd Romaine from the decrepit old yellow bus that Macy and I had ridden into town on the days when neither my father nor my mother could be cajoled into driving us to school in one of their air-conditioned cars. After eighth grade, Mother had insisted that Daddy get me a car and an emergency driver’s license so Macy and I more or less escaped having to ride the school bus on a day to day basis after that.

Lloyd had been a farm boy who wore the same pair of scuffed cowboy boots, often caked with mud, to school every single day for at least three of the four years that we attended high school together. Unfortunately, I possessed absolutely no memory of his alleged younger brother Floyd, the man who held me firmly in his grip at the moment, nor could I recall any salient facts regarding other Romaine siblings that might have existed during my growing up years. One of the consequences of constantly reinventing my public image is that, over time, it has become harder and harder for me to recall which facts from my childhood are actual truths and which are, as Mother used to say, lilies that I gilded. “Y’all lived on the farm down the road from us, didn’t you?” I asked, buying time to conjure up additional details about the Romaine family. They’d raised cotton perhaps, or maybe they’d had cows? Dairy cows, perhaps? That would explain this man’s extremely firm grip. Perhaps he, like his brother, had milked cows and mucked out stalls before school all of those years ago. Perhaps he still worked with his hands. That fact might explain why his hand felt as if each finger possessed a plier-like tension that periodically tightened and released around my bicep. I did remember that the older brother Lloyd had not participated in sports, because he went straight home after school Mondays through Fridays to help out on their farm. I did not like to be caught off-guard like this. Once again, I tried to pull the top half of my body out from under Floyd’s weighty arm, to no avail. With his left hand, he held on to me. With his right hand he raised the plastic cup emblazoned with the official Cypress Springs Fire Department Seal on one side and the words Crystal and Rocky inscribed on the cup’s rim to this mouth. Frothy beer foam spilled down the sides of the cup.

“That’s a fact, little lady,” Floyd said, smiling widely, bobbing his chin downward to the point where it seemed to touch his chest, as he gave my shoulders yet another squeeze.

“Is Lloyd here tonight?” I asked. I am never at a loss for words, but I was really stretching it here. One of my key core principles is, like a good trial lawyer, never to ask a question to which I do not already know the answer. Life is simply safer that way.

Finally, Floyd released his grip on my shoulders. He took one step backwards, and bent forward at the waist until our eyes were on a level plane. He moved robotically, as if his joints had become stiff and inflexible with age. It bothered me to know that he was younger than I was. He had old age brown spots on the backs of his hands and his oversize nose was crisscrossed with broken blood vessels. “My brother Lloyd died in Viet Nam. He didn’t come back. I thought you would have known that.”

I felt as if this large man, who now stiffened his posture upright again and squared his shoulders with resolve, had just sucker punched me. I wished that I had known that one little fact about his brother. “I’m so sorry for your loss,” I began, switching into funeral language mode.

Unbeknownst to me, and even though the music had inexplicably stopped, Macy and Carlton had joined us on the dance floor and now stood directly behind me. I heard her gasp of horror and didn’t have to turn my head to understand that, as usual, my sister was shadowing my every movement. Macy may not be a party person, but all her life she has been a first class worrier. She reached out her hand and clutched onto the back of my dress. Whenever Macy Rose got scared as a child, she glommed onto something soft and warm, preferably something that belonged to me. It seemed unlikely that my little sister would have known of Lloyd Romaine’s death and failed to tell me about it. But how could Macy not have known this fact? Unless Lloyd had stayed in the army for a long time, Macy would still have been living in Molly’s Point when the death occurred.

“Lloyd wrote you a letter before he died. My mama still has it in the box that the army sent his possessions home in. I wanted to bring it to you, but when the letter came, well, that was after you’d already run off to Hollywood to become a movie star. So my daddy said, ‘give it a rest, boy, delivering that letter won’t bring your brother back.’

“Oh,” I said. What possible words could I have spoken at that point?

Some people believe in ESP, others do not. Quite frankly, I don’t care whether people believe in extrasensory perceptions or not, I am well aware that they exist. Just as I was wondering if the Romaine family still lived down the road from us, Floyd Romaine answered that question. “We didn’t own that land. We only were renting it, so after my daddy died, with Lloyd already passed on, my mama gave up farming. I was already living in Cypress Springs by the time that happened.”

“Oh,” I repeated. Now Macy was tugging on the fabric of my skirt. I wished she’d let up on the scared little girl stuff. I turned around to face her and very gently removed her hand from my garment. “Really,” I said. I was vaguely aware that people were standing around, clustered into little groups, drinking, talking, waiting. Waiting . . . what was that about, I wondered?

Macy wasn’t the only one from the group of us who had caravanned over from Molly’s Point who appeared to be on the verge of having a conniption fit. From snippets of conversation that I could overhear, Carlton and Curtis were caught up in a conversation about shotguns and skeet shooting and didn’t appear to be at all concerned that something weird was going on with Floyd Romaine. However Nina, ever my sister’s copycat, had obviously overheard Floyd’s last words and now she was giving me the big eyes as well. What would the two of them suggest that I do at this point, cut the poor guy dead? “So very very sorry. I truly didn’t know. Please give your sweet mama my sincere condolences,” I said, for want of any better words occurring to me. At that point, I did the only thing that I could think of to do at that point, I changed the subject. “What brings you to the wedding tonight?” I asked. Either he was friends with the bride or the groom, I thought. Probably the groom, since I was related to the bride’s side, and I hadn’t ever heard of any of us being related to anyone in the Romaine family.

“Both. I church with both of the kids’ families,” Floyd responded.

I said nothing, but I must have telegraphed my confusion to Floyd because he followed up his previous statement with these words: “I married a Cypress Springs girl. I’ve lived here for the past twenty-two years. We live out on her family’s farm, one of them anyway.”

“Oh,” I said, knowing that I wasn’t sounding particularly loquacious at this stage of the conversation. I kept trying to think and discovering that I was unable to conjure up a visual image of Lloyd Romaine. I didn’t believe that the dead brother had looked anything like this man who was standing in front of me. “Well, why don’t you introduce me to your wife?” I finally managed to squeak out.

Floyd put his plastic cup, now empty, down on a table set up to receive dirty dishes, rubbed the palms of his hands together, and utilized the moisture left over from the outside of his drink cup to finger comb his hair back off his sweaty forehead. “Let’s go,” he said. He took hold of my elbow and pointed me in the direction of a table across the room, steering me toward the opposite side of the room as if he were propelling a wheelbarrow across a lawn. “Her name’s Jamie Sue. Used to be Jamie Sue Galloway. She’s from here. I already told you that though,” he said.

I’m really halfway decent at interviewing people, and to this day believe that I could have had a television career as an investigative journalist. I cocked my head off to the left and gave my bright characteristic smile, and told myself that I was doing just fine. I began speaking with animation to Jamie Sue, smiling and looking forthrightly in the eyes, signaling to her that I was interested in her, and not in any way after her husband, who for some reason appeared to have propped his left arm across my shoulders again, and, although he no longer maintained the ironclad grip on my upper arm, did appear to have forgotten that he had more or less anchored me in his grip. Some big men just don’t recognize their own strength and that is the truth.

I had just learned that Jamie Sue worked at the bank her family owned, one of the banks that her family owned, and was wondering just how rich her family actually was, when Floyd startled me with this exclamation. “Hey! There’s someone else here tonight that you know. You remember Ralph Anderson, don’t you? That’s him, sitting right beside my wife. Son of a gun, Claire Louise, you recognize your old boyfriend, don’t you?”

I’d started to tune out Floyd’s words, having ascertained that he was one of those sort of men who is basically shy, although, after he’s had slightly too much to drink, he becomes loud and effusive. I continued to smile at his wife; I noticed that she wore what I took to be a vintage cameo ring on her right hand, no doubt a family heirloom with great sentimental if little monetary value, and a plain gold band on her left hand. The heavy silver cuff that she wore on her left arm instead of a wristwatch was encrusted with chunks of turquoise. Mexican jewelry can be very deceptive. My guess was that the piece that Jamie Sue wore had been purchased at one of those roadside gift shops on the road to Albuquerque. Perhaps she’d gotten it from one of the vendors who set up outside the museum in the town square, but I thought it unlikely that the piece had come from one of New Mexico’s better jewelry shops. All that I could see of Jamie Sue’s body was her top half. She looked to be slender and wiry, but that was just a guess on my part. The bracelet looked almost forlorn on her thin wrist. I couldn’t see Jamie Sue’s feet or legs as she was seated at a table across from where I stood, but the starched blue denim western shirt with pearl snap buttons that she wore had her name, Jamie Sue Romaine, and the words First State Bank of Cypress Springs, Texas embroidered on it.

“I like your Petit Point Silver and Turquoise bracelet,” I said. “It’s Zuni, right? And I’m guessing maybe from the fifties?” Always err on the side of caution, I reminded myself. Pretending as if you think that an object comes from Neiman Marcus even if you’re dead sure that it hails from Target at best is never a bad conversational gambit.

She looked confused. Her husband still, or again, had his arm tight across my back. I kept trying to forget that he was present and the man kept intruding himself upon my presence. As Floyd contracted all of the muscles in his arm, I could literally feel each little sinew through the cloth of his shirt against the bare skin of my back. Then he vise-gripped inward with the fingers of his hand, crushing the right side of my upper body into his own middle section. “Well, Claire Louise? Aren’t you even going to say hello to Ralph?” he prompted.

“Ralph?” I repeated. That one word sent alarm bells jangling throughout my entire body. I stiffened and reached up with both of my hands to grasp Floyd’s entire left arm and shove it forcibly away from me. I was literally panting at this point, trying to get air into my body, and I felt as if I’d just crossed the finish line of a 10K race in which I had pushed myself to an all time personal best. My ribs compressed around my heart and lungs so intensely as to render me unable to inhale so much as one complete breath. I hadn’t heard Ralph’s name spoken aloud over one or two times during the twenty years since I’d been back in Molly’s Point. I held my eyes steady on Jamie Sue’s face as I struggled to draw enough air into my lungs to enable me to answer Lloyd’s question. “Ralph, of course I remember who he was,” I said, speaking through a constricted airway that rendered my words both hoarse and strangulated-sounding. I didn’t desire to take my eyes off of Jamie Sue’s face. Frantically, I tried to remember the point where the two of us had left off in our conversation. I cautioned myself to breathe, and take my time, but most of all, to proceed with caution. Beyond that, if I managed to pay careful attention to what I was doing here, I should be fine. I would bring my conversation with Floyd’s wife to a logical conclusion, as I slowly and carefully made my exit. I believe that at any given time we are likely to have guardian angels all around us. Just then, despite the roaring in my ears, I heard a voice that I didn’t recognize and that was originating from some point external to my own brain, and that was unlikely to be audible to anyone other than me, say, “Keep your cool. Smile. Say some polite innocuous words to that woman, whoever the heck she is, make your excuses and leave the room. Don’t run away. Depart with dignity.”

Floyd continued to harass me with words that literally made no sense whatsoever. At least his arm no longer rested across the top of my shoulders. I felt my entire body erupt into a cold sweat when Floyd, speaking slowly as if talking to a person of limited intelligence, said, “That’s Ralph Anderson, right across this table from you.”

I now realized exactly what was amiss with Floyd Romaine. The man had to be a closet sadist, at the least. I swiveled my head around to stare him down. “Ralph Anderson is dead, Floyd. He’s been dead every bit as long as your poor brother has been dead. So do me a favor and cut the crap, why don’t you?”

Unless the man was a world-class actor as opposed to a first class buffoon he couldn’t have manufactured the shocked expression that appeared on his overly large face. So this wasn’t a complete set-up. That was good to know. Floyd’s eyes widened, his nose broadened and reddened, and he opened and shut his mouth several times before he spoke, “Ralph’s right there, across the table from you, Claire Louise.” His words trailed off, and then, when I continued to stand straight and still and to maintain a steady gaze directly at him, he added, “next to my wife. That’s him.” He laughed weakly. “He’s not dead that any of us have noticed.”

Frantically, I searched my brain for a possible explanation to this madness. Momentarily I was trapped in my own past, seventeen years old and four months pregnant and the baby due to arrive after football season, but before basketball season, right around Christmas actually, so if I played my cards right, I thought that I would be able to conceal my pregnancy at least long enough so that I wouldn’t be forced to resign as head cheerleader before the end of the football season. However, if Molly’s Point got into the play-offs this year, which was highly likely, then the team might keep going on into December. This had happened before, as Molly’s Point has always had good football teams, and it could very well be that I was going to be have to come up with a plan B.

First things first. Mother was getting suspicious and even though I didn’t want to, I had decided that I was going to have to clue Ralph in regarding my situation. I waited until Mother and Daddy had gone to bed and Macy had turned off the television set and switched on the box fan in her room before I crawled out my bedroom window and walked out across the main road to the dirt road across from the highway to town where Ralph was waiting for me. This wasn’t the first time that I’d slipped out of the house to meet a boyfriend, but as events were to transpire, it did turn out to be the last time that I ever had to sneak out of my own house.

Ralph wasn’t inside his mother’s ten-year-old Ford Fairlane sedan. The car was parked across the road, where Ralph always waited for me, but that was the last normal thing that happened that evening. Ralph’s mother sat in the back seat, a passenger in her own vehicle. Sheriff Oates sat behind the steering wheel, his hands positioned at the ten and two o’clock positions as if he were actually sitting in a moving vehicle as opposed to a parked car. My father, his hands folded across his chest and his legs straight out in front of him as if he were sitting in his recliner at home in front of the television set, sat in the front passenger seat. I didn’t understand any of this until after I opened the door and bent over to explain to Ralph that I was running fifteen minutes late because Macy Rose had decided to wash her hair and wind it up on foam rollers before she went to bed, which was ridiculous because she was going to be getting it wet all over again in the swimming pool first thing in the morning.

“Not so fast, Missy,” my father said, and at that moment my world began to crumble in all around me.

“Where’s Ralph?” I demanded. I was scared, but he didn’t cow me. The days of my father intimidating me were long over. Or so I told myself.

“Get in the back seat,” Daddy said. “Or turn around and get yourself back inside your own house,” he said.

I couldn’t think. The overhead light in the dark blue car wasn’t illuminated, as the light bulb had burned out recently and Mrs. Anderson hadn’t replaced it. Even so, I could see that she’d been crying. Her entire face appeared to be streaked with tear tracks and the skin around her eyes was puffy and swollen. She’d had a perm that week and her wiry gray hair stood out in little corkscrew curls all over her head. Sheriff Oates looked grim. “Honey, get inside the car and let’s talk a little bit,” he said.

The car only had two doors, so Daddy had to step out and push the back of the front passenger seat forward so that I could climb inside the back seat next to Ralph’s mother, who like Sheriff Oates, didn’t appear inclined to look at me. “Where’s Ralph?” I repeated. I knew my rights. I was seventeen, old enough to legally emancipate myself in the state of Texas. Ralph was eighteen years old, old enough to be drafted and go to war, which was what he had been worried about because he wasn’t in school and he didn’t believe that he could even enroll in mechanic’s school unless he finished his high school diploma which he really didn’t want to do. It’s at this point that the events of that evening, actually of the subsequent years, grow hazy and difficult for me to recall. I was sitting in the back seat of Mrs. Anderson’s car, next to her, and Sheriff Oates and my father were in the front seat of the car, one of them looking solemn and the other looking cynical. One of the three of them, I’m not sure which one actually pronounced the words, but one of them said, “No nice way to put this. Ralph is dead. He was down at the rodeo in Cypress Springs last weekend. You remember that, right? He was bull riding and he took a bad fall. He got up just fine, and walked off, but he must have had a concussion, best we can figure. He just didn’t wake up this morning.” Whichever one of them did the talking that night, neither of the other two adults in the car contradicted the words that were spoken. They were three grown-ups to my one seventeen-year-old pregnant person. Why would I have questioned the veracity of the statements they made? I didn’t. I believed them. Ralph’s mother looked completely devastated and Sheriff Oates looked official and honorable. I don’t recall actually seeing my father’s face after I got into the car with them. At that point, I believe that I simply passed out in the first legitimate dead faint of my entire life.

I swiveled my eyes from Lloyd, past Jamie Sue, to the two individuals who sat to her right. There was a roaring in my ears that made it difficult for me to think, much less hear the words that were being spoken around me. I recognized Ralph’s wife first; she was the white-headed woman with the young-looking face who had spoken to Macy and me in the restroom earlier that evening. The way she’d pronounced our names, Claire Louise and Macy Rose Richards, she had sounded as if she’d first seen our names and pictures on the wall at the police department. She’d backed away from us as if she’d been told that we were likely to be both armed and dangerous and as if the APB out on us warned any individuals encountering either or both of us not to approach but to call authorities at the first opportunity. Her hair was cut in a pageboy cut, with bangs, in exactly the same style that I’d worn my hair during the summer before my senior year in high school, before I ran away from home to become a movie star. She and I stared at each other, neither of us blinking. Only when I saw her eyes fill with moisture could I force myself to turn my head another fifteen or twenty degrees toward the left. The man seated beside the white-headed lady with the young-looking face wasn’t Ralph. He simply could not be. Involuntarily, I felt my head begin to shake from left to right. This man was smaller in stature, and his features were chiseled and sharp as if there was literally nothing beneath the skin of his face other than angular bone. His eyes were glacier blue and cool and emotionless. I looked from him, back to the woman he sat beside. His arm was around her, and they wore matching gold bands on their left hands. I frowned. He looked like a man who might have been related to Ralph; perhaps he looked like Ralph’s father, although I had never met Mr. Anderson. “Ralph Anderson Junior?” I asked.

“That would be our son,” the woman replied. Now her eyes, like her husband’s, the exact same blue as the man they were saying was my old high school boyfriend telegraphed gritty determination. Could both of them be wearing contact lens, I wondered? Because Ralph’s eyes had been steely and hard, like my Daddy’s but they’d been a hazel, almost green color. Macy Rose had been right, I shouldn’t have been hitting the bar quite so hard this evening. I hoped that I wasn’t fixing to barf all over these people.

I felt my head began shaking violently from left to right. I couldn’t force the roaring in my head to stop. “No, no, that’s not possible,” I began. I fought to make my voice calm and reasonable. There was an explanation for this. There had to be. “Ralph Anderson died. A concussion. He didn’t wake up,” I said. I think I remember those words actually coming out of my mouth before I fell forward. I crashed into the table, dropping to earth almost literally in front of the two of them. Did I say any other words at that time? I don’t believe that I did. Maybe, before I passed out, I said, “They lied to me. They told me you were dead. They all lied to me.”

Ralph’s eyes widened in surprise. Perhaps that is the last thing that I remember before I fainted. I said, they told me you were dead, and he said nothing in reply. I think that perhaps he and his wife both looked at me with some sympathy, and then they looked down at the plates that sat on the table in them. Maybe that’s what happened last, I was looking at the tops of their heads as they avoided looking directly at me. I cannot tell you how much I hate it when people feel sorry for me. That is an emotion which, under no circumstances, can I abide. Other people’s sympathy; I hate that. I noted another random odd fact at that point, namely, Ralph’s wife’s hair wasn’t naturally white-blond, she’d obviously bleached it, as along the part line, front to back, starting at her bangs and running all the way across the top of her head, plainly visible, was a quarter inch line, dark brown roots. She bleaches her hair, that’s the last thought that I can recall before I came to approximately fifteen minutes later, outside the fire station, laying on a stretcher in the back of an ambulance, hooked up to some sort of cardiac monitor. I will say this, if a person is going to pass out and have her sister shrieking and screaming that she’s just had a heart attack, then the fire house is the exactly best place to be. Because the firemen, trained paramedics, and all their equipment is right there along with you. I believe that it only took them about thirty minutes to discern that there was absolutely nothing wrong with my heart.

Macy says that people are saying that I planned the entire ugly scene. They think that if I’d really and truly fainted my knees would have buckled and I would have collapsed where I stood. What appears to have happened however is that when I passed out I fell forward, as if I was propelling my body across the table, toward Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Anderson. The end result of my forward motion was that when I blacked out, I fell onto the table; I literally crashed into Ralph’s wife and Jamie Sue Romaine. Naturally, most of the people seated around us at that moment jumped to their feet, causing the table, tablecloth, and all of the food, beverages, plates, cups, and eating utensils to end up in the middle of the floor. Many of the people seated at adjourning tables, in the act of backing away from the table that I’d fallen upon, pushed against their tables, the end result being that five of the seven long tables on that side of the room collapsed as well. People fell down, and were helped back up. There was a significant amount of screaming.

My sister, watching the entire sad scene unfold from our table across the room, had been unable to hear any of the actual words spoken, but she saw me shove Floyd’s arm away, and she could tell that I was upset, and when she observed my body begin its descent toward the table, she rushed to my rescue, believing that I was having a heart attack. This was not at all an unreasonable thought on her part. Two of our uncles on Mama’s side died of heart attacks. Both of the men simply stood up one day, one from the kitchen table having just finished the bacon and eggs his wife had prepared, and the other from his recliner, somewhat annoyed as the remote didn’t appear to be functional. Each of them assumed stricken looks upon their faces as they keeled over dead. Unfortunately, Macy was the only one from that side of the room to observe what was transpiring across the room, so when she jumped to her feet and rushed to my aid, her foot collided with one of the table legs at the table where she was seated, and she elbowed Carlton against the side of his head as he tried to slow her down, the end result being that their table also collapsed and Macy only made it to a point about two feet into the middle of the room, functionally, the dance floor, before she slipped on what was likely somebody’s spilled drink, and crashed to the concrete floor herself.

She says she never lost consciousness, and she’s really sorry about that, as she’ll never be able to forget the consternation on the groom’s face or the hysterical laughter that erupted from our cousin, Crystal San Miguel. She’s glad, of course, that I didn’t have a heart attack and die, but she says that once she realized that I’d only fainted, she felt like killing me herself.